YNYSLAS

Poems by Gareth Jones

Buy ‘Ynyslas’ Kindle Edition on Amazon here

Poetry has accompanied me from earliest years; at school I was teased for talking in verse.

This was nothing exceptional for the Welsh, whose language elides one word with the next by phonetic mutation resembling spoken music; but in English it raises eyebrows. When the hwyl takes hold – a form of ecstatic utterance shared by preachers, poets and penitents – there is no stopping the flow.

The ancient Celts of Britain and elsewhere were despised as illiterates by their Roman colonisers but much sought after in Athens and Rome as teachers of rhetoric to the young. Whence this paradox?

The lack of a script fostered something different: ingrained memory, flawless recitation, recurring patterns and not least inspired improvisation demanding fluency and passionate persuasion.

The collection Ynyslas, though scripted not improvised, is designed to be spoken – performed even – in this bardic tradition of oral transmission, which releases the narrative and emotional progression through dramatic interpretation, preserving such debts to cynghanedd as unobtrusive internal rhyme and disguised alliteration, verse skills now largely abandoned in ‘free form’.

The past comes closer, childhood is ever present; the unconscious reasserts itself and life cycles re-emerge from crowded memory; absence and loss obtrude more painfully. Ynyslas deals with all this.

These are mostly long poems by contemporary standards, often disguising a story, studded with dramatic re-enactment and dialogue, in the manner of Welsh poets from Dafydd ap Gwilym to David Jones, whose Anathemata and In Parenthesis were read to me by my father.

Unlike film, poetry requires no consent, no finance, no third party. Only a voice. And a wilderness…

Ynyslas

1960 and the nuclear age hit North Wales in the form of Trawsfynydd Power Station built on our doorstep. Having witnessed the atomic explosion on Bikini Atoll, and suffered health consequences that would haunt him till his death, my father had no desire to remain. His Wales had been blasted by concrete and worse might follow. In his absence on duty for the BBC in Tokyo that summer, my mother took her four children in search of a new home, further south, and found it not far from the magnificent beaches of Ynyslas that fringe the Dyfi Estuary…

Read and listen to the poem Ynyslas here.

Immoto Perpetuo

In his pastoral elegy Lycidas Milton laments the drowning of a young man off the coast of Wales. The poem is suffused with sadness and absence, in the manner of Poussin’s Et in Arcadia Ego of the same year, 1638/9. My daughter has lost a young friend and suddenly the universe seems empty. Four hundred years later the cosmos offers a chillier landscape to Milton’s bucolic rêverie.

Read and listen to the poem Immoto Perpetuo here.

Going to Switzerland

Tracing the passions and ideals that shaped or dislocated the past, one is tempted to surf for the half-forgotten lover of yesteryear. A harmless nostalgia, one might think. But instant information comes at a cost.

Read and listen to the poem Going to Switzerland here.

Berlin ist nicht so weit

An uprooted childhood can be liberating or traumatic, sometimes both. My remove to Berlin aged seven at the height of the Cold War with my father, BBC Foreign Correspondent Ivor Jones, would define the rest of my life. The compulsion to return has never left me. My degree, doctorate, screen work have all been marked by the German language and long periods spent in Germany over many decades. One time frame merges with another; earlier visits blend into the next, as if one had never left. But memory falters while life moves on; absence is sometimes not retrievable.

Read and listen to the poem Berlin ist nicht so weit here.

Vol de nuit

All travel carries an element of danger, though as passengers we try to suppress it. Air travel is fraught with hubris we ignore at our peril. Poets are notoriously insomniac: risks taken and wagers pledged return as nightmare to torment one, a nocturnal fall from grace in keeping with Gustave Doré’s Lucifer, after Milton, once again…

Read and listen to the poem Vol de nuit here.

Vol de Nuit is based on a real event but with a complex genesis which the following may hint at:

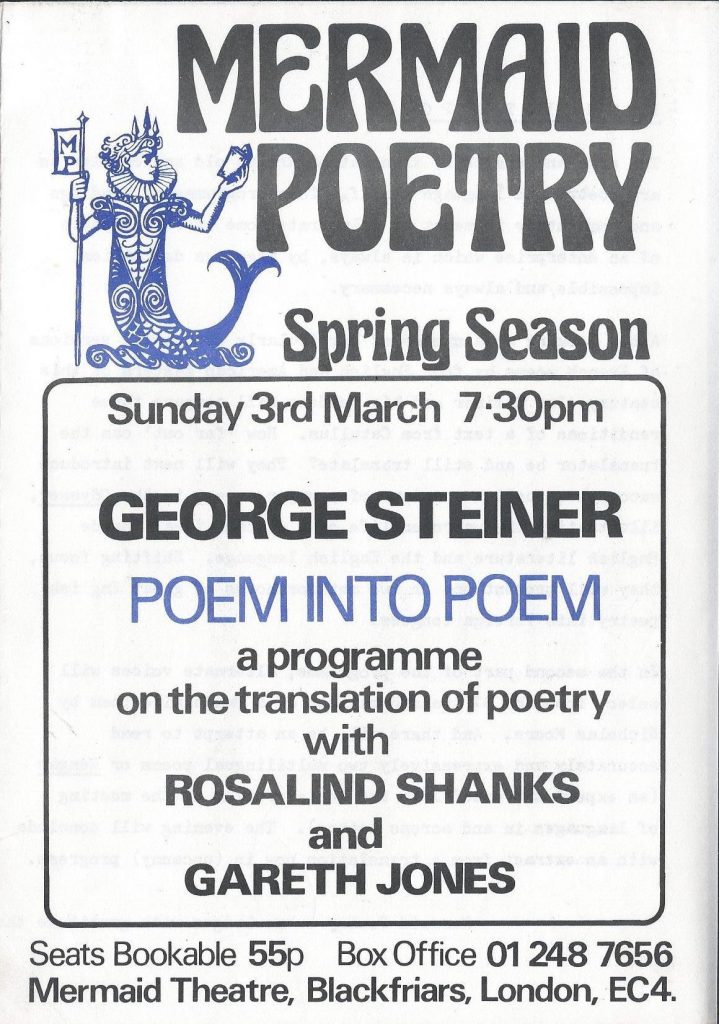

March 1974. The Mermaid Theatre, London, a short walk from the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, then still on Henry Carpenter Street, Blackfriars, where I was finishing a post-graduate course before taking up a trainee directorship with the Prospect Theatre Company.

March 1974. The Mermaid Theatre, London, a short walk from the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, then still on Henry Carpenter Street, Blackfriars, where I was finishing a post-graduate course before taking up a trainee directorship with the Prospect Theatre Company.

My recent Cambridge supervisor George Steiner, who knew me as a linguist and an actor, had invited me to take part in a poetry reading of his devising, Poem into Poem, as one of two readers.

His theme, provocative as everything George thought and did, was that even the best poetry can be improved by translation.

Rosalind Shanks was to read the originals, leaving the German and French translations to me. These included a miraculous Le naufrage du Deutschland from Gerard Manley Hopkins’s The Wreck of the Deutschland. To my shame I have no record of the translator, which is telling in itself.

Hopkins was himself a polyglot. He wrote in the Welsh language (as well as in English) and understood many more. His cymraeg inspiration has been undervalued by critics with no access to the original text. The translation of his greatest poem brought this home to me. The Wreck of the Deutschland reads more Welsh in French.

It was to be half a century before I dared investigate my own response to a more recent manmade disaster that has haunted me, as that ill-fated vessel the Deutschland haunted him. My debt to Hopkins is clear and acknowledged in Vol de Nuit, though pudeur or simple decency demands the comparison end there.

George Steiner’s commitment to translation, to language and literacy, was radiant and inspirational.

The multi-culturalism to which I have devoted much of my filmic life, in part through George’s example, must welcome multi-lingualism as its natural pendant.

I make no apology for the linguistic diversity of this and other poems. Language is life blood. Transfusion. English has nothing to fear.

Time

Some say that poetry is nothing without emotion. I would reply that words have their own emotion separate from their author. Words can build a poem as inanimate bricks build a palace. So Time might seem only an elaborate verbal jest. A sequence of jagged monosyllables numbered off to the timing of a metronome, counting down to the present. Many of the words are no longer in use. Others are neologisms. Unpoetic. But that is the point. The poem recruits whatever language it finds and mixes archaic and actual in promiscuous union to explore the passage of time itself. Though no emotion is apparently expressed, reflection implicitly discovers it.

Read and listen to the poem Time here.

Epidavros

Archeological visits need not proceed without irreverence. After all, ancient tragedy was complemented by a light-hearted satire offered on the same bill. This visit, however, revealed a secret. Theatre was medicine, yes. But medicine was also theatre. When prayers failed, divine intervention might require human assistance. A performance. Nowadays we would regard this mystical hoax as quackery verging on scandalous abuse. But Oria’s quickening is recorded with gratitude, in stone still visible today. Hopeless credulity? Or something more subtle?

The priestly intercession of ‘Dionysos’ in rites of fertilization was perhaps transparent, just as artificial fertilization is today…

Read and listen to the poem Epidavros here.

All Hallows

It is generally assumed that nothing of one’s early months is retained in the adult mind. But the child’s mind retains impressions recorded as a babe in arms… Child memory illuminates moments too easily discarded.

Read and listen to the poem All Hallows here.